You have likely heard about the total solar eclipse crossing the United States from Oregon to North Carolina next Monday. Perhaps you’ve made plans for a trip to somewhere on its path to see it for yourself, or maybe you’re an astronomer or other scientist planning for serious study.

As AT&T’s official historian, my thoughts turned to past eclipses and what AT&T might have done to observe or study them.

Research in the company archives led me to the total solar eclipse of Jan. 24, 1925. This eclipse crossed part of the Northeastern United States, from Buffalo, New York, to the eastern end of Long Island. The northern part of New York City was in the path of the total eclipse, and the rest of the city saw a partial eclipse.

Astronomers planned to observe and time the eclipse at 5 stations across the route. They had AT&T’s assistance, not only in assuring the stations would be connected by telephone, but also in accurately timing the eclipse as it crossed the sky.

AT&T engineer Warren Marrison worked in the company lab in New York. He was a leading expert in developing accurate clocks.

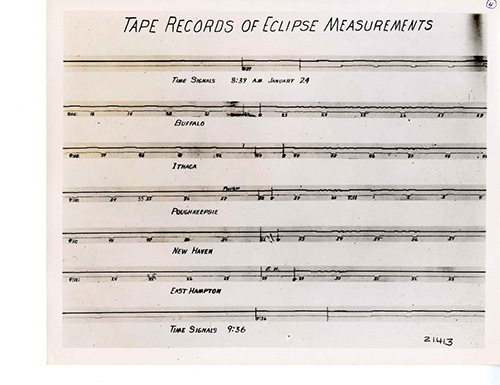

Marrison arranged to have each research station along the route send him a telegraph signal at the moment they first observed the moon’s shadow completely cover the sun. Marrison’s recorder noted the time on narrow rolls of moving paper, thus creating a record of the eclipse’s route accurate to a fraction of a second.

Marrison’s crowning achievement came in 1927 when he invented what was at the time the most accurate clock in the world—the quartz clock. It is the direct ancestor of the watch you may be wearing on your wrist.

(Caption: Marrison’s record of the time of the eclipse. Courtesy AT&T Archives and History Center.)

AT&T also sent groups of researchers to spots along the eclipse’s path to measure the eclipse’s effects on various types of radio transmission.

Radio was very important to AT&T in 1925. It was just a few years after the start of radio broadcasting. AT&T operated 2 of the nation’s first radio stations, one of which, WEAF in New York, broadcast from within the eclipse’s path.

Also, AT&T was in the final stages of developing what would become in 1927 transatlantic telephone service with calls crossing the ocean via radio waves. Radio was also important to the U.S. Navy, which solicited AT&T’s assistance in studying radio and the eclipse.

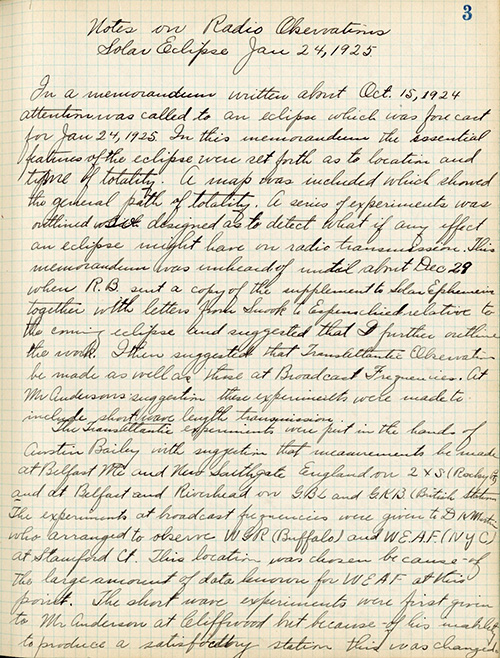

AT&T scientist George Southworth traveled to Greenpoint, Long Island, New York, to record in his notebook the effects of the eclipse on short-wave radio transmissions from New Haven, Connecticut. Like Marrison, Southworth became better known for a later invention—the millimeter wave guide, which became an important component of radar systems in World War II.

(Caption: The first page of Southworth’s notes from the time of the eclipse. Courtesy AT&T Archives and History Center.)

Sheldon Hochheiser, Ph.D. - AT&T Corporate Historian