By: Bill McSorley and Brian Freeman

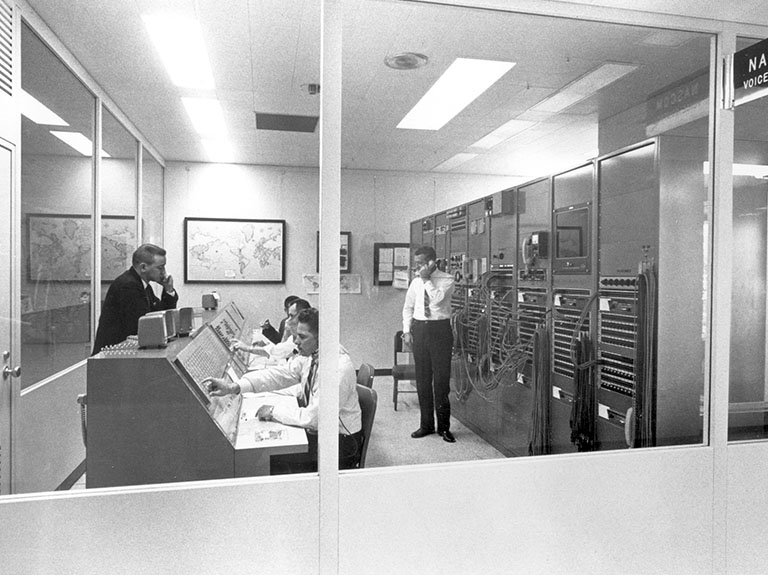

An early 1A Electronic Switching System in Dublin, OH in 1977. Photo courtesy of AT&T Archives and History Center.

It’s likely you spent the morning of June 3, 2017 in routine fashion. You probably woke up, sipped your coffee, and groggily celebrated the end of another long week. But for AT&T, those early hours marked the end of an era.

On that Saturday, we sent a team to the Lincoln Central Office in Odessa, Texas to decommission the last 1A Electronic Switching System (1AESS) in service. Forty years ago, these switches were the call center work horses of our landline network. And while only a handful of these switches remained in operation after 2010, the 1AESS and its predecessor – the 1ESS – were once cutting-edge technology. They helped us use our phones in new ways.

Pick up your iPhone or Android. Take a look at its standard calling features. It takes a quick swipe to activate call forwarding or call waiting. A tap of the screen to switch to another call. A few seconds to add your friend to your current conversation.

These features may not seem that revolutionary now. But in the ‘60s and ‘70s, the advent of electronic switching systems launched capabilities like 3-way calling, speed dialing, call holding and call forwarding into the mainstream.

So as we say goodbye to this historic piece of wireline technology, let’s take a look at the evolution of electronic switches and how they helped get us to where we are today.

It all began at AT&T’s Bell Labs.

It was the 1960s. The era of space travel, lasers and touch-tone telephones. “Hello, operator?” had become a thing of the past. More importantly, computing was propelling mankind into a new age of communications.

And we were on the forefront of telecom innovation.

At 12:01 a.m. on May 30, 1965, AT&T forever transformed the way we make calls by creating the first electronic central office switch, the No. 1 ESS – or “1ESS” – in Succasunna, New Jersey.

The original 1ESS in Succasunna, NJ. Photo courtesy of AT&T Archives and History Center.

In his speech during the dedication ceremony, AT&T Chairman Frederick R. Kappel punctuated the significance of the ESS for the future of calling.

“Just as the Telstar satellite showed the way to new achievement in intercontinental services, so this electronic central office is the forerunner of a new era of convenience for our neighborhoods and our nation,” he said. “The strength of America’s communications system lies in what we call the ‘switched network’ – in the tremendous number of inputs and outputs, its great speed and versatility, and its ability to connect any user anytime with any other. ESS is going to do this job for us better, faster and – in time – cheaper than ever before.”

The power of this new, electronically switched network was tested moments before Kappel’s speech, when New Jersey Governor Richard Hughes initiated the first use of “Add-On” – or 3-way calling – by dialing U.S. Secretary of Commerce John Connor into his call with Louis Nero, the mayor of Roxbury Township, New Jersey.

While its various custom calling features made the system revolutionary in its own right, the ESS also made us the first phone company to use computers to direct calls. That was like making the leap from car phone to smart phone overnight.

But the concept for the computer-controlled electronic switch was hatched long before that day in 1965. Let’s rewind a few more decades.

The idea for an ESS was conceived prior to World War II. More impressively, it came about before the invention of the transistor – the device that made this entire innovation possible (and one also from AT&T Bell Labs).

It took 20 years and the creation of an electronic switching organization, various trials in Morris, Illinois and, finally, the official commercial launch in Succasunna to bridge the gap between concept and reality. It was the single largest development effort Bell Labs had undertaken to date.

After that first successful call in New Jersey, the ESS began replacing Bell System switches in central offices in densely populated areas nationwide. While the initial switch in Succasunna served only a fraction of its capacity potential, the 1ESS greatly expanded our network capabilities.

By 1974, the 475 1ESS offices across the nation served almost 6 million landlines. Each office could serve up to 65,000 lines and switch nearly 100,000 calls an hour.

But the 1ESS required a lot of space. It consumed a large amount of energy. So in 1976, we introduced version 2.0 of local electronic call switching – the 1AESS.

With the crossover to the 1As – a quarter the size of the 1ESS and much more energy efficient – we went from serving as many as 65,000 lines per central office to over 100,000. At peak hours, it could handle up to 250,000 calls an hour. It also allowed faster processing speeds, call billing functions and more custom calling features, including several catered to business customers like Centrex and PBX.

This was also the first time an out-of-band signaling network was used. This network added the first set of software-defined network (SDN) features with what was, at the time, the super-fast speed of 1,200 bits per second. Today, we think of SDN as a new, IP-based technology, but the basic concept has been in the AT&T network for over 40 years.

Modernizing our network.

Chairman Kappel predicted in 1965 that all switching in AT&T’s central offices would be done electronically by 2000. And while he may have missed the mark on our technological advances since then, he got one thing right. AT&T has continued to be the leader in network innovation.

Throughout the decades we continued serving our home and business landline customers by slowly converting our technology from analog, to digital, to IP-based systems.

But our network has changed exponentially in recent years.

In the past, adding new calling features, programs and capacity into our existing hardware equipment was a reliable method for expanding our capacity and calling features. But that was when voice was the sole player in network traffic.

For years, the busiest day of the year for our network was always the same: Mother’s Day. If you could build a voice network that could handle the rush on that day, you were in good shape.

That’s no longer the case. Now, as the network has gone mobile- and video-centric, the busiest day of the year can be any day. We also talk not only about busy days, but busy seconds. As the network gets faster and faster, our customers expect it to operate faster, too.

We’ve been vocal on our network transformation, including how our software and 5G worlds will collide.

Software, in particular software virtualization and software-defined networking, is the only way to stay ahead of customer demand. Our goal is to virtualize 75% of our core network functions by 2020 through our network function virtualization (NFV) program. We’re also implementing next generation SDN to operate those virtualized functions more efficiently and to give our customers direct control of their network services. Powering it all is our network operating system, called ECOMP that will enable us to operate and upgrade those software-based virtualized network functions more efficiently

The only constant is change powered by innovation. That’s as true today as it was in the 1960s – at the dawn of the ESS era. Even with our last 1AESS now decommissioned, it’s a reminder that we always have to be preparing for the next big thing.